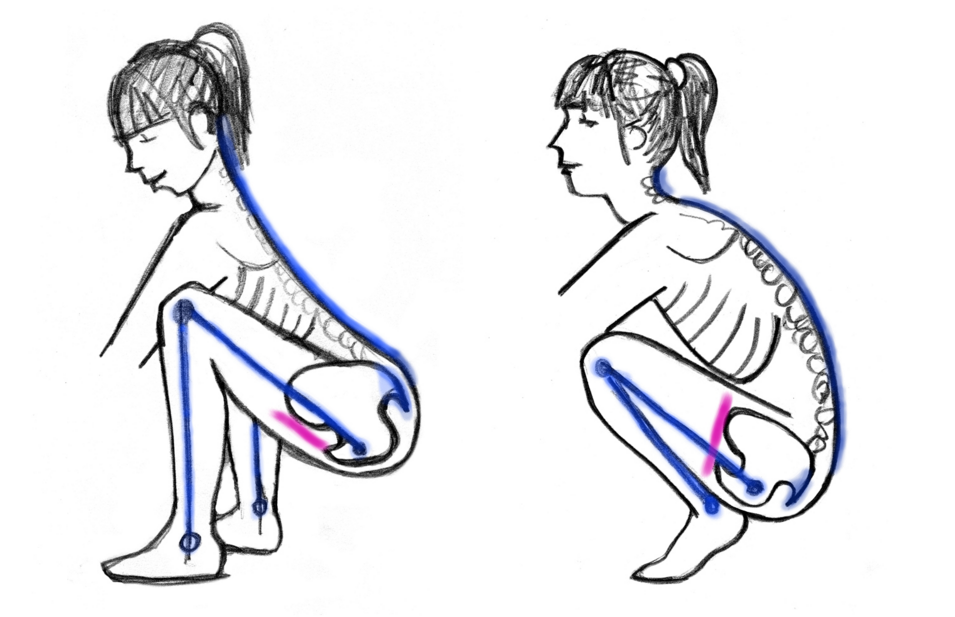

Now that we have officially left Breast Cancer Awareness Month and the pink ribbons have been tucked away for another year, perhaps it's time to think not just about research to cure cancer but also the importance of lifestyle measures that take the etiology of breast cancer into account. The fate of our cells is strongly associated with the state of our inner environment. This is why we take so many strides towards optimizing that environment by eating well, getting exercise, and avoiding environmental toxins and known carcinogens. But is there more to optimizing our environment to support healthy breasts? As scary as breast cancer is, what we currently understand about cancer may give us an edge in beating the odds. A contemporary understanding of cancer acknowledges that our bodies are constantly working against cancerous and pre-cancerous cells and that the environment we provide our cells with can be either a risk factor or a preventative factor in helping those cells normalize. According to hormone-specialist Dr. Sara Gottfried, it's "lifestyle, genetics, immune functioning and nutrition that determine whether those cancer cells grow or get removed by your personal army of immune cells." But there is another vitally important factor in cellular health: MOVEMENT. Research done at UC Berkeley has recently shown that breast cancer cells respond to movement, ie. loads, forces, touch, and sensory input. How amazing is that? "While the traditional view of cancer development focuses on the genetic mutations within the cell, Mina Bissell, Distinguished Scientist at the Berkeley Lab, conducted pioneering experiments that showed that a malignant cell is not doomed to become a tumor, but that its fate is dependent on its interaction with the surrounding microenvironment... We are showing that tissue organization is sensitive to mechanical inputs from the environment at the beginning stages of growth and development,” said principal investigator Daniel Fletcher, professor of bioengineering at Berkeley and faculty scientist at the Berkeley Lab. “An early signal, in the form of compression, appears to get these malignant cells back on the right track.” ( source ) These scientists are actually teaching the world about something called mechanotransduction , "the process by which cells sense and then translate mechanical signals (compression, tension, fluid shear) created by their physical environment into biochemical signals, allowing cells to adjust their structure and function accordingly." ( source ) Mechanotransduction explains that touch itself can provide a direct mechanism of action that will affect the chemical communication of cells in the body. And it's not just touch, because all sorts of forces and loads affect cells. Every load is a unique distortion of a cell. Even gravity affects cells. Since we know that gravity remains locationally stable (except in Interstellar ), perhaps the most relevant question that we can ask here is whether/how our movements have changed over time, and how that might impact breast health. We already know that modern semi-sedentary lifestyles decrease the health of our circulatory system, including the heart, and they negatively affect our metabolism and blood sugar regulation as well. Stagnation in the lymphatic system (which has no central pump and requires mechanical movement in order to work optimally) has a negative impact on our immune function as well. Our diseases of modernity strongly correlate with our lack of regular frequent natural movement, or basic movements that we would have made in naturelike flat soled walking, squatting, reaching, hanging, carrying, climbing, unassisted sitting, and sleeping on firm surfaces. The most logical question might be: is the etiology of breast cancer really that different from these other modern diseases? Consider all the ways, both cultural and environmental, that we have altered the loads to our breasts and their surrounding muscles and tissues. Modern behaviors reduce movement in the shoulder girdle, shorten the pectoral muscles, and create restricted range of motion in the glenohumeral (shoulder) joints. Stress creates patterns of breathing that activate the scalene muscles of the neck and the traps which lift the collar bone to increase lung space instead of allowing for the full body wave of breath that would be activated by a healthy diaphragm and a relaxed nervous system. The natural wave-like movement of healthy breathing exerts its own unique force on the tissues of the chest, thoracic spine and abdomen, creating movement in the ribs and underneath the breasts and potentiating micromovement through the upper lymphatic pathways that keep them flowing. If this is simply the effect of healthy breathing and alignment, what happens when we consider the altered tissue dynamics created by tightly constricting bras, carrying bags on one shoulder, wearing organ-compressing shape-wear or clothing, and many hours of computer use and right-angle chair sitting every day? What happens when we consistently restrict the musculoskeletal system? Aside from creating stagnation in the lymphatic system, tissues eventually bond together with a "connective tissue glue" comprised of fascia; we create adhesions that even further restrict movement. Your neurology creates a new "set length" for your muscles too. Yeah, your body magically makes you more "efficient" because you aren't using that range of motion! Now you require less muscular energy aka. less ATP and glucose to remain in that fixed state. So, what's the biomechanical answer to better breast health? More and better quality movement. - Incorporate more natural movements into your life: every day, every hour. Include carrying, hanging, climbing, flat shoed walking, stretching, diaphragm release, full body breathing, conscious relaxation (resolution of the stress response), and squatting. In order to create health, we have to move the body as a whole but for upper torso health, hanging/stretching the arms overhead for even ten seconds every few hours is a great start. Try to do it while keeping your torso in alignment and without lifting and flaring your ribs, even if your arms don't lift as far. - Practice chest opening poses to counteract the shortened pectoral posture created by computer overuse. Restorative yoga poses that open the chest are wonderful. My favorite pose is this restorative exercise floor angel (I picked the most entertaining video.) The beautiful thing about this pose is that when you're done moving your arms and are ready to relax, as long as you have your bolster correctly placed (no lower than your shoulder blades) you're in a perfect position for psoas release which is prime deep relaxation/deep breathing territory. You can stay here 5-20 minutes while you allow the rib cage to slowly drop down towards the floor. (No effort-ing it down.) - Stay HUMAN. Even laughing and singing have a vibrational affect on the tissues of the lungs and chest, so let's include lifestyle habits that promote joy. Watch funny movies and drag your friends to karaoke! Allow yourself to cry. All of those membranes swell and then resolve giving your system a good flush. - Manually stimulate your upper lymphatic system with self-massage . - Touch your breasts. Not just to palpate them for lumps, but to know them. Notice how the texture and firmness changes with the ebb and flow of your hormone cycle. Nipple stimulation and oxytocin release could be a factor relating to lower rates of breast cancer in women who breastfeed . - Develop a relationship with your relaxation response. This program is one I practiced and taught for more than a decade but there are many others. Find a restorative yoga class. You don't need to learn special yogic counting and breath retention as much as you need to unlearn the holding patterns and increase the tone and flexibility of the muscles that support healthy respiration. Holding patterns are related to stuck and held emotion, which is another reason to stay loose, not sweat the small stuff, and increase pleasure in daily life. Cheers! There is really nothing that is guaranteed to give you an easy birth. You can watch tons of Orgasmic Birth videos, listen to only happy and empowering natural birth stories, get massaged every week, work with hypnosis, and be fit as an Olympic athlete and still have an unpredictable labor. Alternately, you could be extremely lucky and do absolutely nothing to intentionally prepare for labor but magically be one of the fast precipitous birthers who labors for four short hours and never finds it unbearable. As with most things related to the human body and experience, there are complexities and outliers and nothing is certain. But that doesn’t mean that preparing for labor doesn’t give us better outcomes. It absolutely does; and regular movement practice leaves us stronger and better prepared for whatever labor has in store for us. Biomechanist Katy Bowman explains movement for birth like this: If you want to train for a marathon, you’re going to need to run a lot. Being an excellent swimmer or gymnast won’t prepare the specific muscles needed to compete in a marathon, because that’s not the way our bodies work. You may be at peak fitness in one area, but totally unprepared for a different kind of athletic rigor. Birth is essentially a natural athletic event that most modern women are underprepared for. Many of the reasons for this are deeply ingrained in culture, and culture helps to shape our anatomy. While women have been birthing naturally for thousands and thousands of years, one important question to ask ourselves is how have our bodies changed during this time? For one thing, our western lifestyle has decreased the natural mobility in our bodies, especially in the pelvis. Before I go on, let’s take a few moments to get really familiar with the pelvis. The pelvis is actually comprised of four bones: two illium, the sacrum and the coccyx. The bones are joined by connective tissues- namely ligaments and fascia- and these connective tissues are dense but mobile, they should have some amount of GIVE. (Having this in mind is incredibly important to keeping your head together when you consider that a baby is coming through the pelvis for the first time,) In fact, the joints of the pelvis are naturally capable of more movement than you'd think. Their apparent lack of mobility in the western world is apparently based more on our movement habits than genetics. The number one thing that we do to shorten the amount of space in the pelvis is to sit in chairs with our tail bone tucked and our sacrum compressed all day long. This “normal” sitting posture reduces our healthy lumbar curvature and decreases pelvic floor strength dramatically. Most of us are familiar with the term pelvic floor by now. You probably have some ideas of how to strengthen this area as well because it's taught in every Cosmopolitan magazine and OB’s office. KEGELS! Kegels are the exercise that has been most frequently taught for many decades. And while I hate to rain on anyone’s well-intentioned kegel parade, there are evidence-based reasons why doing traditional kegel exercises in isolation may not be giving you the benefits you think they are. According to Bowman, "A kegel attempts to strengthen the pelvic floor, but it really only continues to pull the sacrum inward promoting even more weakness, and more pelvic floor gripping. The muscles that balance out the anterior pull on the sacrum are the glutes. A lack of glutes (having no butt) is what makes this group so much more susceptible to pelvic floor dysfunction. Zero lumbar curvature (missing the little curve at the small of the back) is the most telling sign that the pelvic floor is beginning to weaken. Deep, regular squats (pictured in hunter-gathering mama) create the posterior pull on the sacrum." Here are five simple changes can make a big impact on pelvic health and alignment which will support feeling strong and empowered throughout your pregnancy and into labor. Your goals should be to untuck the pelvis, strengthen the pelvic floor muscles, learn simple but reliable relaxation techniques, and build strong legs and glutes while keeping your joints in good alignment. More important than doing “reps” of any exercise is trying to make shifts in how we habitually carry ourselves throughout the day. How you hold yourself now — during your pregnancy — also dramatically affects the state of your post-baby body. Take it slowly and always listen to your body. Old patterns are deeply engrained in both the connective tissue and in the neurology through the “set” length of the musculature. *Please be sure to consult with a doctor or midwife if you are uncertain whether these practices are appropriate for you. First change: SITTING (sitting?) If I can give you one priceless piece of advice, it would be to stop sitting on your tail bone the majority of the time! As I mentioned above, we need untucked tailbones for optimal pelvic floor strength even more than we need the isolated contraction of kegels. To shift your weight off the sacrum and onto your “sits” bones, tilt the pelvis forward. This should return curvature to the lumbar spine as well and make you feel like you are sitting taller. One great way to do this more easily is to regularly sit on a cushion that raises the sits bones above the knees or on a foam dome that allows the pelvis to stay dynamic and "awake". Midwives also tell mamas to sit this way as much as possible towards the end of their pregnancy to help the baby’s head get into the best position for labor (facing the sacrum). Second change: SQUAT with intention (see image above) I'm not suggesting you take up quadricep-powered gym squats. For these squats you want to focus as much attention on strengthening the lumbar curve as you can (think: don’t pee on your feet), while maintaining the integrity of the knee and gently strengthening the legs. A proper natural squat requires that all of the joints from our feet to our hips are working optimally, and for most people this is simply not the case. So moving towards an optimal squat may mean beginning to mobilize the ankle joints and lengthen the calf muscles with a half dome ( not this , but this ) or rolled towel, or using the half dome under the heels while squatting. Doing preparatory squats with a chair is a great way to allow oneself to experience the openness and suppleness of the pelvic floor right away. I highly suggest you just go here and read up on squatting because there are pictures and Katy goes into some depth about the mechanics. You can also use the back of the chair to work on doing small pelvic tilts with a straight spine (without bending the knees) while you feel your sits bones moving away from one another and your booty blossoming. It may not feel “lady-like” but it’s building an essential skill for better birth. Here's a video . Third change: Move DIFFERENTLY We are creatures of comfort and habit. Though the joints and articulations of the body are capable of (literally) innumerable configurations, we tend to get comfortable as adults using the least amount of effort to move in predictable ways, which ultimately begins to limit and constrict us (and ultimately contribute to degeneration). This is your invitation to re-inhabit your kid body. Sit on the floor. (You will find yourself wanting to stretch, naturally.) Stretch your body long like a cat in bed before you start your day. Put on your favorite music (music with a stronger beat helps) and dance in your bedroom. Get the hips and booty moving. We tend to equate fluidity with sensual movement, so feel into your beautiful sensual pregnant self, even if it means faking it until you make it. Remember that pelvic floor disorder is most prevalent in western and european countries, where we sit in chairs a lot more and move (and squat and booty shake) a lot less. (Please start doing this now so I don't have to keep myself from saying "I told you so" in five, ten or twenty years.) Fourth change: RELAXATION as an essential practice Relaxation is not optional. It is an essential part of your movement practice just like the spaces between these words are essential to legibility and ease of reading. A day at the spa is luxurious and wonderful, but often expensive and impractical. But I highly recommend that you find a way to receive nurturing massage from a pregnancy-trained therapist (like me) whenever you can. Massage releases hormones of relaxation and contentment that even your baby will experience. (But avoid painful deep bodywork as any extended mama pain can potentially decrease oxygen to the baby.) Aside from getting massaged when you can, it is equally important that you learn to relax throughout the day. Until I create my own, I recommend this guided meditation from my Restorative Yoga Mentor Jillian Pransky. A prenatal yoga class can also allow you to tune in to your body and your baby, and provides one setting for nurturing relaxation. As much as we want to strengthen the pelvic floor, we also want to deepen our capacity to release those muscles so the baby can get out! Fifth change: WALK WALK WALK Take movement breaks, walk short distances instead of driving (or park at the back of the lot), and try so very hard to make movement a part of your daily experience. Walking may be the most important movement that you do. It strengthens our core musculature, our glutes, and our legs, supports circulation, moves the lymphatic system, and creates healthy cellular loads. As you work towards optimal pelvic alignment and greater symmetry, you will find that walking becomes easier too. Research also indicates that "for women with normal pregnancies, physical activity is accompanied with shorter labour and decreased incidence of operative delivery." The key is to engage in "submaximal weight-bearing activity" which includes walking, hiking, using a treadmill, or stair stepping.  Liberated Booty on the banks of the Ganges Liberated Booty on the banks of the Ganges

I’ve spent a good chunk of the last few months immersed in Katy world. Katy Bowman, that is. A number of years ago this sassy scientist wrote her thesis on protocols for the pelvic floor, and she determined based on both research outcomes and mechanics of the pelvis that (in isolation) Kegels don’t do squat. In fact, they do FAR less than squat because they may simply create tension in the pelvic floor instead of strength. She determined that what we need is SQUAT and we need A LOT of SQUAT. Because currently 80% of the western world will suffer from some form of pelvic floor disorder in their lifetime!

But being a legit scientist, she didn’t just tell people to squat a lot. She explained that modern western life has made proper squatting incredibly difficult. All that right-angle couch sitting, and desk sitting, and car sitting… Before most of us can get to an optimal squat, we have to realign our bodies, starting at the feet. We have to align our feet, train our ankles, lengthen our tight shortened calf muscles, and eventually learn to keep our shins vertical (!) and use our now lazy booty muscles instead of relying on our quadriceps. We need to keep our pelvis anteriorly tilted (bowl pouring forward), maintaining healthy lumbar curvature so that our tailbone is reaching up/back(ish) and not pointing between our feet. In short, there is no in short. Katy Bowman’s proper squat is in the details, and there are many; the preparatory squats are basically utkatasana on ‘roids. According to lady Katy it can take a year of solid preparation for many people to really get down. For most people these details are overwhelming enough to simply ignore. Power Vinyasa isn't the only hard. Slowing down is hard. Micromovements are hard. J. Brown wrote a post about this a few weeks back calling for a Slow Yoga Revolution and it was awesome. One, because it’s really hard to actually experience "yoga" when you are flailing your limbs about choreographically. But even more so because getting into the core instead of just performing fast Simon Says style yoga geometry is actually harder on every level. We can do a great deal of fakery with the outer body that keeps us from having to delve more deeply into our core musculature, mindset, or emotional states. But it’s much harder to fake micromovement; it is much harder to fake SLOW. Microyoga requires our presence and attention in a very real way, because there is no dance to do and there is no faking it. That magnifying lens can be very strong and very yogic, if you let it be. You know what is harder than slow yoga? Changing your habits. It’s much easier to go to yoga class a few times a week than it is to get into the daily grind of avoiding lazy habits. Yet habits are where the body is made and broken. Take the habit of sitting on your tailbone instead of your sits bones/ischial tuberosities. Our modern lives are generally set up for us to fail at this. Cushy couches curl our spines and compress our sacrums, and the habit of leaning back into the lumbar spine is a hard one to break. Our hamstrings tighten over a lifetime of sitting with our legs at right angles, perpetuating the cycle in a positive feedback loop of poor alignment doom. The sacrum moves anteriorly as we push on it, creating slack in the pelvic floor and leading to disorder. Now you need more yoga to try and work on those hamstrings, which are pulling at your back, and more squats for your pelvic floor. But what if instead of rolling out our yoga mats, we kept them rolled up under our butts every day and sat up off those tailbones? What if instead of choosing the fluffy couch, we sat on the floor more often or built a standing desk? How can we re-make our lives and our culture to support vitality in a way that is less overwhelming and more about small supportive daily habits? Ayurveda is a big fan of health-supportive daily habits or dinacharya. This is probably because the vaidyas were aware of the profound effect that small daily actions have on our lives. It’s strangely easier for many of us to go on a crash diet, to go to exercise class, or to go on a meditation retreat than it is to take 5 minutes to regularly relax and find our breath, to reconsider dietary excesses, or to adjust our alignment. I counsel myclients regularly on the necessity of making their workspaces more ergonomic, of not working on their laptops while in bed, of not wearing high heels excessively because their spines and knees are suffering from the added force. But it’s hard. They want me to rub out their crimes and sins against the body. But no one can undo in one hour a week what we spend 12 hours a day working at. Our bodies exist within straightjackets of culture and “normalcy”. When I was studying physical theater in San Francisco I got really tuned in to these postural masks. Our city culture asks for our complicity in this linear march. It asks that we move predictably, and without any hint of the fluid body or animal within us. It asks us to renounce organic functionality (and fun, and joy) in favor of constriction: bras, belts, ties, and heels remind us of this bondage. Above all it requires that we reject emotion, because the one thing that we are never allowed to be is fully embodied, wild, spiraling, emotional creatures. (We could say so much more about that, but I digress...) Until the recent booty fetish, “nice” women have been hiding their booties and tucking their tailbones with an almost religious fervor. Yet a good indicator of pelvic floor disorder according to Bowman, is “flat butt”, or underdeveloped glutes, tucked tailbone/posterior pelvic orientation and reduced lumbar curvature. Has our normative-female culture deactivated our underdeveloped glutes to the point that we have weakened our pelvic floors so significantly? In order to reclaim the health of our pelvic floor, we are going to have to start by reclaiming our booties, or as my friend, the visionary space activator Binahkaye Joy says: we need to liberate the booty. This is not about fetish or vanity but SERIOUS SELF-CARE. Embracing the health of our backsides helps to keep our core fired and takes some of the load off the psoas. Squats that emphasize glute activation increase the strength of the pelvic floor and help keep the sacrum in alignment. For the health of our pelvic organs, our metabolism, and our elimination, building the booty is a high priority! That doesn’t even get into how important it is for labor and birth....but let’s save that for another time. For now, I leave you with this. Turn on your best bootyshakin’ music, take a hike in the hills, go slow, and change a habit that could literally change the course of your life. Give yourself permission to be your wild bootylicious self.  Pro Athlete Gabby Reece getting YogAligned Pro Athlete Gabby Reece getting YogAligned Last night a dear friend of mine sent a few words my way. After a brief chat about my latest blog essay he finished with "your love of yoga almost inspires me to get on the mat...almost." I immediately wondered what he thought my practice looked like because I don't think we have ever discussed it. I also empathized because I understand why people who love yoga also avoid yoga, and it I’m fairly certain it has less to do with being lazy than they imagine. As diverse as the multi-brand yoga community likes to think it is, the general conception of yoga practice is still pretty homogenous. It's based on the idea of the hour/hour-and-a-half long practice of stretching and strengthening your body as it goes through various complementary poses with the goal of doing some twisting, inverting and side bending, and concluding with a yogic nap. There has been a general trend towards sweaty vinyasa and Bikram-style classes, I suspect, both because of the amount of endorphins released (natural high!) and because of the street-cred that these yang-type classes tend to garner. The Lilias Folan style hatha yoga of yore just doesn’t have that same edge. While there is definitely an increasing market for restorative and yin classes these days, that's a part of the point too: people like extremes. We also like hot bodies, and by hot I mean: fat-free, symetrical, and with genetically predisposed joint flexibility. Since Instagram photos of these hot bodies in various stages of contortion are all the rage these days, I often have a hard time identifying with the yoga culture of our times, and I know I'm not the only one. Yoga teacher training is an industry that preys on young people who don’t know what to do with their lives but want to do something meaningful. In the world that we live in, it would be hard to blame anyone for trying to find their meaningful niche. Yet, the devotion of trainees often becomes something deeper than that. Unfortunately, in the process of becoming yoga teachers, many get indoctrinated into the belief system of a "lineage". They begin to speak about aspects of their yoga as if they were speaking truth from heaven, with the full authority given to them by being a card carrying member of that lineage. They find yoga salvation. One of my favorite recent discoveries has been the writing of Carol Horton PhD, a former professor of Political Science turned true yoga badass. Referring to recent "scandals" within some popular yoga brands she says this, "...while we should honor and learn from Indian tradition, we need to recognize and guard against our longstanding tendency to romanticize the “mystic East” and glom onto pseudo-traditional philosophies that promise to deliver us from the challenge of living in 21st century America...we need to stay grounded in the here and now, not sailing off into fantasies about joining some medieval Indian lineage and having “the Universe” smile on us just as we’d like, all the time." There's something insidious about how different yoga brands and lineages work: they indirectly ask their trainees to give up critical thinking. The frightening thing is that most people who stay give it up freely, even joyfully and without coercion, because interwoven in the dogma of yoga asana is the idea of yoga lineage being a direct line to the divine. Questioning the practice becomes about as sensical as questioning the life force energy itself or questioning your guru's credentials. I mean are YOU, in your tiny bud of limited consciousness to question the process of unfolding to a thousand petaled lotus? Well, first of all, you're not a flower. Thankfully there are a growing number of pioneers in the field of critical yoga theory. One of the most maligned dispellers of yoga myth is journalist William Broad, who in his book The Science of Yoga: The Risks and Rewards, manages to piss off a right handful of powerful yogafolk. In a quote from an online interview Broad says , “Yoga is surrounded by this certain mystique. Even though people know that it’s not that, they still love the existence of the mystique. The idea of perfection. Spiritual perfection, physical perfection, and anything that shakes that mystique is bad. Right? But to me, that’s like the Roman Catholic church sweeping the bad priests under the rug. There’s just going to be more victims.” And though he’s not the first to tackle yoga history, he does outline the history of the practice of American yoga asana, which he explains, finds its inception not in the ancient temples of India but in the 19th century as a derivation of calisthenics taught by the British Military mixed with Hindu religious philosophy and used as a contortionist showpiece of Indian nationalism. This is the origin story of Iyengar, Ashtanga, and all of their yoga lineage babies. What this really conveys to me is that modern yoga tradition is created by real people. Does that make it any less useful? Absolutely not. Not if we are willing to discard the dogma and keep what is supportive. Yoga isn’t the only Indian discipline to suffer from this “true believer” syndrome, its sister science Ayurveda is chalk full of regional and cultural knowledge that is interpreted as having holy and unquestionable origins. For example, there is one esteemed Indian Vaidya (doctor) who likes to talk about how bananas clog circulatory channels, and another that tells her followers never to eat watermelon. (I’d like to set up a date between the Vaidya and the raw foodie girl who eats 30 bananas a day; they should garner equal incredulity.) While there may be specific historical, cultural, meteorological, or epidemiological reasons for the Vaidya coming to that conclusion and thus dissuading his followers from eating bananas, most critical Ayurvedic practitioners are going to "dance" a bit when you bring it up. It makes Ayurvedic methodology, which can actually be a very sophisticated way to approach bioindividuality, look pretty kooky in light of the fact that a large portion of the worlds population gets their caloric needs met by eating bananas. Another problem with making something sacred or believing in its ancient spiritual origin (without potential of fallibility) is that we feel personally responsible when it isn't working for us, and instead of changing the yoga to fit our needs, we feel like we are lazy or wrong for not doing it; in fact your reason for abstaining from the practice could actually be that it's not good for your body. -- Modern yoga visionary Paul Grilley is a teacher’s teacher. While I hear that term thrown around quite a lot these days, in Grilley’s case it seems wholly apropos. Paul Grilley is one of teachers revolutionizing yoga training through evidence-based practice. His yoga trainings in anatomy provide students with incontrovertible visual evidence of anatomical diversity, specifically as it relates to joints. (Though I don't think that he uses his understanding of anatomical diversity very well in the context of marketing his Yin Yoga brand...naturally flexible people can do themselves a great deal of long-term harm by focusing on expanding their connective tissue.) Joints are perhaps the most vulnerable parts of our structural human anatomy, and joints are protected by ligaments. Ligaments are dense connective tissue structures that connect bone to bone. When muscle has released itself to the point of relying on ligaments for support, we risk damaging our joints and the connective tissues that surround them. In engineering terms, ligaments are plastic, not elastic. When you take a piece of plastic bag between your fingers and stretch it apart, it warps - there is no going back. These are essential protective structures that support the health and longevity of our movement, and with luck and safe use will continue to do so into the golden years of our lives. We need to protect them. In his popular DVD, Grilley presents viewers with a diverse assemblage of volunteer yogis, and he shows how each of them have a unique joint structure that often prevents their yoga asana from looking “correct”. He also shows that a person trying to make their asana look the way their teacher tells them it should look can actually cause significant joint and ligament damage over time. For those who might still be unconvinced, or attribute the participants limitations to “inflexibility”, he provides something that an ex-anthropology club member like me just eats up: bones. It is hard to argue with someone who can show you with bones that the difference in available and healthy range of motion (ROM) between one person’s shoulder and another’s can be more than 45 degrees. If you hate downward dog, this could be part of the reason. It could also be because if you aren’t bone-on-bone at the edge of your ROM in the shoulder joint, you are likely “hanging from the ligaments”, an offense that Yogalign teacher Michaelle Edwards has critique for aplenty. Edwards has been refining her yoga method for more than twenty years into a book and a methodology she calls YogAlign. As a bodywork practitioner and yogi she asks a lot of very valuable questions about why we practice yoga and whether the yoga practice we do is supporting pain-free movement in the rest of our lives. She also contextualizes the needs of modern western bodies, explaining that in a society where we spend much of our time in chairs and with our bodies at right angles, we tend to suffer from overuse issues stemming from these positions, and many popular yoga poses create these very same tension patterns. Edwards says, “Because of high injury rates and the fact that these poses are not ancient and time-tested, I came to the conclusion that we all must take a look at yoga asana (positions) and assess their biomechanical value…it is vitally important that the essence of yoga- know yourself- is not lost in a physically-based practice that makes no biomechanical sense.” (source) Her method integrates principles of deep core breathing, fascia lines, moving from center efficiently, and maintaining healthy spinal curvature. She also challenges one of the core unspoken tenets of asana practice: that relaxed stretching of a muscle leads to flexibility. “Muscles need to be tightened in order to become flexible, and to stay safe we need to tighten them when we stretch; we also need to keep the body comfortable so that we do not invoke the stretch reflex.” Edwards also uses resistance stretching or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF), a technique that re-calibrates the nervous system’s set point for muscular flexibility. If all of that relaxing, breathing, and static stretching in yoga class wasn’t bringing you much closer to the flexible-ideal you were seeking, this may be why. In his book Stretching Scientifically, Thomaz Kurz makes me question why flexibility outside of the range of what we need for healthy everyday movement is even desirable. “Great flexibility alone will not prevent injuries. Actually, excessive development of flexibility leads to irreversible deformation of the joints, which distorts posture…” “In choosing your stretches you should examine the needs and requirements of your activity.” He expands on this by talking about athletes in different sports and the importance of specific flexibility training. One quote that hit home for me had to do with external rotation of the hip joint, which is most easily seen in Baddha Konasana, or butterfly pose, something that is easy as pie for my naturally open hip joints. “Unbalanced flexibility… may contribute to injuries. In classical ballet, where dancers have an extraordinary range of external rotation and abduction of the hip combined with less than normal internal rotation and adduction, 30% of dancers complain of lateral knee pain and 33% of anterior (front) hip pain. In nonathletic people, a range of external rotation in the hips greater by more than 10 degrees than the range of internal rotation is associated with low back pain.” While we often focus on opening the hips in yoga, how often to do we consciously think to internally rotate the femur to create counterbalance? How many of us know that our hips are already so open that focusing on internal rotation might be more structurally balancing?" -- Let’s get back to that rogue journalist William Broad. One of the beautiful things that Broad pointed out is what I want to call the Original Sin of modern yoga: it tried to use scientific language to legitimize its practices without the research to back it up. Easily one of the biggest yoga fibs that came out of this postulating relates to what is happening when we breathe. Broad explains, “No matter how fast or slow you breathe, you can’t change the amount of oxygen that you take into your body. That’s contrary to many yoga teachings.” I’m sure this misinformaton was contrary to many basic physiology and kinesiology teachings as well, yet why the truth of it eluded yoga teachers for so long seems to be another instance of: that its just the information that was passed down the line. We were all playing parrot. In the all of the pranayama training I have ever done, this increased oxygen fallacy has been used to explain the relaxation response that comes from deep breathing, and the reason for doing full abdominal or three-part breathing. In fact, I am somewhat sad to admit that its what I taught to students myself for many years. In the more vigorous pranayama techniques, the exact opposite is happening, we are increasing our levels of CO2. This is not to say that pranayama isn’t useful; elongating and slowing the breath has clear benefits, particularly relating to vagus nerve stimulation, and you can find plenty of great research supporting it. The point I am making is that the teaching, like many others, was just something that was made up by an ordinary person. A conjecture at a mechanism of action that was passed off as absolute truth. -- There are a growing handful of yoga teachers and organizations that are paving the way for a more anatomy-informed yoga practice. Leslie Kaminoff, Jill Miller, Paul Grilley, Michaelle Edwards, Brea Johnson, Jenni Rawlings, Lauren Ohayon, and Linsday McCoy are all paving the way for yoga practices that make more biomechanical sense and cause less harm. Each of these teachers has their own unique take on how to create a safe and sustainable practice. But for every leaf flowing down the anatomically-oriented river, there is a stick in the mud who still wants to push you into positions that are going to overstretch the ligaments in your spine. As teachers we cross the ethical threshold when we lose our humility and pretend to be something we are not. We must keep learning and keep challenging. -- My own journey into practice has been roundabout, and sometimes my best yoga teachers didn't even teach me "yoga"... In my early twenties I was spending a weekend with one of my dearest friends in Topanga Canyon outside of Los Angeles. She lived on a gorgeous piece of land with a few other people, and one of those people was Olaf Hartmann. Olaf was an interesting guy to me. For all I could tell, he lived in what seemed a lot like a cave. He had a big open space where he did various movement forms like Chi Gong and cultivated his life force. Olaf radiated life. I still remember a conversation that I had with him one night in passing because he said something that no one before that moment had ever told me. Very impressed with Olaf’s physical prowess, I lamented that I wished I had the discipline that he so clearly had. I told him that I often chose to sleep in rather than practice in the early morning hours like a good yogini. He asked me if I found my practice pleasurable. I was stunned. I told him something to the effect of: Um…kinda, I mean, I feel better after I practice, and I thought that yoga was about fighting against our lazy unconscious impulses anyway… He gave me his million dollar smile and simply said “Try moving into pleasure. When you wake up in the morning you don’t even need to get out of bed, just move your body in ways that feel pleasurable…luxuriously like a cat, and just see how long you want to continue.” I have remembered that encounter for all of these years for one reason: it was a game changer for me. Suddenly I looked at my practice with new eyes: how could I make this practice about moving into pleasure? It instantly dropped me into myself, my breath, and that moment in my body. This was not about hedonic pleasure but about expansive healthy movement. I think that Olaf’s gem of wisdom probably saved me from experiencing more yoga related injury than I have. It also helped to keep me honest about what feels good in my body, which is more often that not what is truly healthy for me. My practice these days maintains the spirit of yoga, but only some of the form. I find myself dropping into my needs in the moment a lot more, getting curious and playing with life. I do self-massage with tennis balls and I “roll out” my body with foam rollers. I do a full practice if I’m in the mood, but more often I take time here and there to pause and expand. I treat my joints with care. I let the energy roll through my body and up my spine as I wake it up through the movement of my hips. I micro-meditate at any time of day, in the shower, and while drinking tea. I do alternate nostril breathing on occasion, but more often I “breathe into” my floating ribs and thoracic spine- thats where I tend to find a little tightness. I move in silly ways, awakening my “kid body”, I walk on the floor on my hands and knees to rebalance my hips and spine, I handstand, I laugh… and I often spend a chunk of my morning moving into pleasure from the cozy comfort of my bed. Right now my life is about moving into yoga much more than “doing” it. And that's sustainable. |

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE:

Movement: The Next Frontier For Breast Health? Five Movement Habits for a Better Birth (that don't involve Kegels) A Tale of Two Booties: The Pelvic Floor, Biomechanics, Culture, and Breaking Bad Habits Sustainable Yoga: How Modern Yoga Practice Often Fails The Test of Biomechanical Value |

Photo used under Creative Commons from euthman